Firstly, it is important to understand that all Annual leave is the property of the employee, not the employer.

Annual leave is accrued at 8% of the employee’s gross pay and after 12 months of continuous employment becomes entitled leave.

An employee can request to use their accrued balance prior to the 12-month mark when it becomes entitled leave. However, it is up to the employer if they want to approve this leave in advance.

Pros:

- Keep business liability down.

- Employees has access to sufficient rest and recreation, reducing risk of harm.

- Useful tool for nurturing a harmonious employment relationship.

Cons:

- As accruing leave is not exact, there can be a risk of running into negative balances.

- Sometimes when the employer goes out of their way to assist the employee by providing annual holidays in advance, they turn around and decide not to come back or leave prior to reaching 12 months of continuous employment.

While there are avenues within the Wages Protection Act 1983 to deduct annual leave in advance overpayments from the final pay, it can be very beneficial to have an accruing leave balance policy built into the Individual Employment Agreements (IEA) to outline exactly how an employee can take this accrued leave and keep it consistent between all staff.

Managing excessive annual leave balances can be slightly trickier.

As entitled annual leave is a liability, it is good practice to review balances regularly, to avoid this getting to high.

It is always good to have clear lines of communication with your employees around their leave. Are they saving it up for a longer holiday further down the track? Is it too hard to take leave due to X Y Z? Would cashing up a weeks’ worth of their entitlement be a good option?

An employer can make their employees take their entitled annual leave in two circumstances:

- They can’t reach an agreement with their employee about when annual leave will be taken, and they give the employee at least 14 days’ notice, or

- They regularly close down for a certain period every year and give the employee at least 14 days’ notice.

When cashing in a week’s annual leave there are a few important things to keep in mind:

- The request to cash up annual leave must be made in writing.

- It will be taxed as a lump sum payment rather than regular income

- You can only cash in a maximum of 1 week of entitled leave each year (based on your annual leave anniversary)

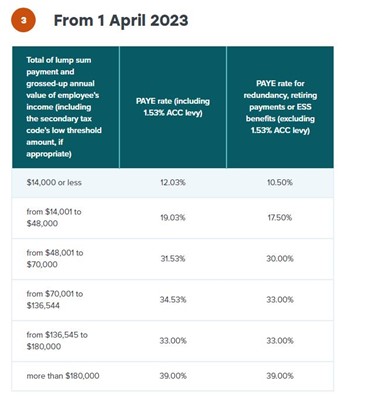

When annual leave is cashed up and paid out as a lump sum, the normal PAYE rates don’t apply. Instead, it is taxed as a lump sum payment.

To work this out, you need to calculate the total earnings for the last 4 weeks ending on the date of the lump sum payment. Multiply this number by 13 to calculate the grossed up annual income value.

This value is then used in the below table to work out the tax of the lump sum.

As an example, Mr Smith is cashing in 1 week of annual leave.

He works a 40-hour week on a salary of $68,000 gross p/a.

He uses the tax code M, contributes 3% to his Kiwisaver and has no other allowances or deductions.

So, his normal weekly pay would be:

$1,307.69 Gross

$278.07 in PAYE

$39.23 Kiwisaver

$990.39 Nett

If he were to cash up a week of annual leave, in addition to his regular salary payment, it would attract lump sum PAYE on the cash up amount, at 31.53%. See below;

$1,307.69 Gross ordinary wages

$1,307.69 Gross AL cash up (one week)

$278.08 regular PAYE deduction

$412.31 lump sum PAYE deduction (31.53%)

$78.46 Kiwisaver

$1,846.53 Nett

In conclusion, a well-managed annual leave account can benefit both sides of the employment relationship. At CooperAitken, our Payroll division can assist you to form good, solid leave balance management habits.

Please call the team for further information.